Researchers at the University of Toronto have developed a tracer ink—a “stem cell tattoo”—that provides the ability to monitor stem cells in unprecedented detail after they’re injected.

The research findings, titled “Bifunctional Magnetic Silica Nanoparticles for Highly Efficient Human Stem Cell Labeling,” was published in June in the Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Already emerging as an ideal probe for noninvasive cell tracking, the technology has the potential to revolutionize stem cell research by arming scientists with the ability to visually follow the pathways and effectiveness of stem cell therapies in the body, in real time.

“Tattoo” tracer can help further development of stem cell therapies

University of Toronto biomedical engineering professor Hai-Ling Margaret Cheng, a biomedical engineer who specializes in medical imaging, says the new technology allows researchers to actually see and track stem cells after they’re injected. Cheng hopes the technique will help expedite the development and use of stem cell therapies.

Working with colleague Xiao-an Zhang, an assistant professor of chemistry at the University of Toronto, Scarborough, Cheng developed a singular chemical compound known as a contrast agent that acts as a tracer. Composed of manganese, an element that naturally occurs in the body, this tracer compound, called MnAMP, bathes stem cells in a green solution, rendering them traceable inside the body under MRI.

Stem cell tracer ink allows long term cell tracking

The contrast agent “ink” first enters a stem cell by penetrating its membrane. Once inside, it stimulates a chemical reaction that prevents it from seeping out of the cell the same way it entered. Previous versions of contrast agents easily escaped cells. By establishing a way to contain the ink within the cell’s walls, the research team achieved the ability to track the cells long term once they are inside the body.

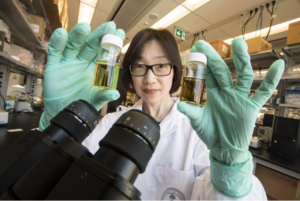

University of Toronto professor Margaret Cheng holds samples of a chemical compound that will create a new way to visualize stem cells inside the body. (Photo: Bernard Weil, Toronto Star)

According to Cheng, some basic contrast agents are already available for use in humans, but none are capable of tracking cells over a long period of time. Contrast agents work by illuminating the deepest and darkest corners of a person’s internal architecture so they appear clearly under X-rays, computed tomography (CT) scans and MRIs. An example of a currently used contrasting agent would be the barium sulfate solution given to patients to help diagnose certain disorders of the esophagus, stomach, or intestines.

The thick substance coats the esophagus and other areas of the body with an illuminating compound, making them visible in an x-ray or CT scan. But the barium solution is eliminated from the body within 2 – 3 days or less. Before the stem cell tattoo tracer ink was developed, surgery was the only option for scientists to get a literal glance of a cells’ destiny after it was injected into the body. Now, researchers can track the results in real time, without resorting to any invasive procedures.

“Before, we could not visually track the cells once they were introduced into the body,” Cheng says. “Now we have the ability to view cells in a non-invasive manner using MRI, and monitor them for potentially a very long time.”

Cell tracer technology still in developmental stage

Currently the tracer ink technology is still in the early development phase and requires more animal testing. Cheng is  hopeful it can proceed to human clinical trials in about 10 years. While Cheng has already proven that tattooing an animal’s embryonic stem cell doesn’t affect its ability to transform into a functional heart cell, rat, or even a pig (which better represents a human’s size), larger models are up for evaluation next.

hopeful it can proceed to human clinical trials in about 10 years. While Cheng has already proven that tattooing an animal’s embryonic stem cell doesn’t affect its ability to transform into a functional heart cell, rat, or even a pig (which better represents a human’s size), larger models are up for evaluation next.

In those test cases, researchers will cut off and reduce blood flow in the animals to mimic the effects of damage caused by a human heart attack. Cardiac stem cells pre-tagged with Cheng’s ink tracer technology will then be injected into the damaged tissue. Using MRI to monitor the luminous inked stem cells in action, researchers can non-invasively follow where in the body they’re traveling and more easily determine if the new cells are responsible for restoring normal heart rhythm.

Before it can be tested in humans, the chemical tracer will also have to pass rigorous toxicology tests to ensure its safety.

###